By Alexandre Bréant and Marc-Olivier Bévierre – CEPTON Strategies

The excitement and controversies that ensued the presentation of the Apple Heart Study at the AAC congress earlier in March show how data generation is evolving in the pharma industry: health data, coming from a non-medical device, harvested by a non-medical company.

How can Real-World data and Real-world Evidence be integrated in pharma companies’ best practice and help them redefine what standard of care means for the medical community and the patients?

Summary

Real-world evidence (RWE) is the evidence derived from real-world data (RWD), which is any kind of health-related data not coming from a clinical trial. Far from opposing to one another, real-world data and data from clinical trials complement each other. Together, they could reduce time to market of innovative solutions, help both the payer and the industry derive better value from treatments, inform clinical practice and optimize treatment allocation to the patients most-likely to have the highest benefit/risk ratio.

However, to realize the full potential of RWD, changes need to happen in both the public (regulatory, payers, healthcare infrastructure) and private side to define the data standards as well as the best practice to collect, consolidate, present and use these data.

With no doubt, companies integrating RWE at each step of the value chain will gain a competitive advantage but this requires an in-depth change in the way data are strategically considered and operationally collected, managed and analyzed.

Introduction

Sometimes, there is merit in comparing apples with oranges. Or more accurately a quart of cider vs. two oranges and a lemon daily, as did James Lind when searched for a cure to scurvy in 1747. Scurvy is a disease resulting from lack of vitamin C that plagued sailors during the Age of Sail. Lind took 12 scorbutic sailors, with “cases as similar as [he] could have them” and split them into 6 groups of 2, gave each group a different treatment (cider, citrus fruits, vinegar, elixir vitriol or mere sea water) and compared the health improvement in each group. This experiment is considered as the first controlled clinical trial [i] and since then, the methods for clinical trials have been refined and improved (blinding of patients and health-care providers, randomization and stratification, advanced statistical analysis, reporting guidelines…) to reach what is now considered the gold standard of evidence generation and the foundation of evidence-based medicine: the double-blind, randomized controlled trial (RCT).

However, while RCT’s praised methodology reduces the risk of getting false positive or false negative results, it does so at the expense of its generalizability to a broader population of patients: for a given treatment, efficacy could substantially differ from effectiveness, as nicely illustrated in the British Medical Journal [ii]. Indeed, efficacy is measured under almost ideal conditions on a carefully selected population in an RCT while effectiveness is evaluated in conditions of clinical practice on the more variable population of patients that exist in real-life.

In an ideal world, data should combine the richness of the real-world setting with the objectiveness of the clinical trial setting. With the increased digitization of the world [iii], will real-world data be able to fulfill this ambitious objective?

What are real-world data and real-world evidence?

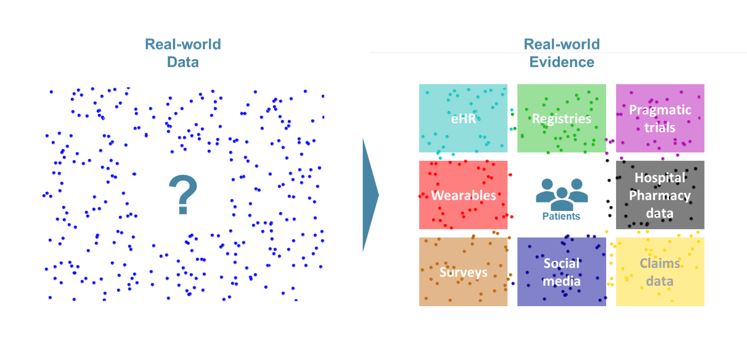

As defined by the Innovative Medicine Initiative (IMI), Real-World Data (RWD) are “An umbrella term for data regarding the effects of health interventions (e.g. safety, effectiveness, resource use, etc) that are not collected in the context of highly-controlled RCT’s”. Real-world Evidence (RWE) is the evidence derived from the analysis and/or synthesis of RWD.

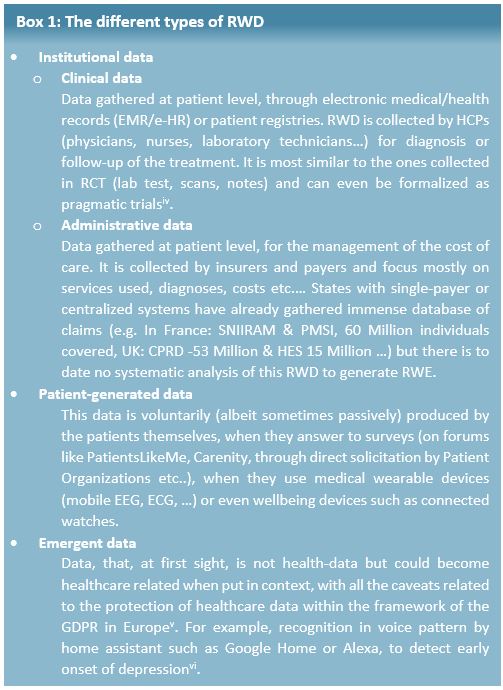

This definition makes it obvious that RWD and data from RCT are complementary subsets of the overall health data available. RWD can come from several sources and be split in 3 different types (see Box 1).

How can RWE be used?

RWD is, fundamentally, data, which means they could be useful, in principle, anywhere data coming from RCT are currently used (regulatory decision for marketing authorization, HTA evaluation for pricing and reimbursement, guideline elaboration and treatment decisions) and even beyond, as it could help empowering the patients.

Regulatory

The primary concern of the regulator is the evaluation of the benefit risk ratio throughout the product lifecycle, so they welcome any reliable information that improves their assessment. Therefore, the EMA considers that, for regulatory purposes “leveraging RWE is a need – and an achievable goal”[vii]. For example, RWE could be used in evidence generation:

– Before marketing authorization (i.e. to obtain new indication or expand indications):

- To demonstrate efficacy (e.g. External control for very rare conditions, complement or even replace RCT [viii] in some cases)

- To enrich safety data

– After marketing authorization:

- For post-approval Efficacy [1] or Safety Studies (PAES/PASS)

- For Effectiveness [2] demonstration

For example, today, home hemodialysis (HHD) is a treatment reserved for young and autonomous Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) patients. However, most nephrologists believe that with smart telemonitoring services HHD could safely be extended to sicker patients (older and/or with comorbidities). In this case, the generation and analysis of RWD on compliance (number and duration of dialysis sessions), efficacy (ultrafiltration rate), and safety (vascular access state) would allow both nephrologists and patients to safely consider HHD as a relevant dialysis modality.

Market access

Payers aim at maximizing public health within the constraints of their budget. This mandate is becoming increasingly difficult with the high price of innovative treatments and the ongoing demographic mutation of developed economies (rise of chronic diseases, increased proportion of senior citizens…).

To optimize spending, they more and more often rely on managed entry agreements (MEA) with pharmaceutical companies, such as value-based pricing or outcome-based contracts. The idea behind the MEA is simple: if a certain level of effectiveness is not met by a predefined deadline, the pharmaceutical company should reimburse all or some of the treatment for that patient.

For example, in 2015 Janssen agreed on rebates on Olysio to the NHS if the patient is not cured within 12 weeks [ix]. To limit the likelihood of a failure (and a rebate), Janssen provided a companion blood test to help predict whether a patient would respond to the treatment, thus limiting the number of patient’s futile exposure to a serious and expensive treatment. Real-world evidence can also be used for pay-for-performance schemes when the situation is not as black and white as the Olysio case, where the cure is the expected outcome. In 2007, a pay-for-performance scheme was negotiated between Janssen and the NHS for Velcade in multiple myeloma. In this scheme, “the company will provide replacement stock or credit for those patients at first relapse who fail to respond to Velcade”, response being measured as the reduction of at least 25% of a serum biomarker [x]. With this response-based rule, Velcade became cost-effective despite their high then-price and was granted reimbursement.

Clinical practice

Improved access to RWE could also mean a continuous and hyperlocal analysis of data, which could guide treatment decision on what works best on specific patient populations:

- Taking into account the geographical, social and personal components [xi] to select a given treatment course or sequence (RWE were cited as the most important data to inform treatment decision, before RCT data, in a recent survey [xii])

- Identify subpopulations or relevant biomarkers [xiii]

- Improve original drug schedule to improve efficacy and or adverse event management [xiv]

Patient empowerment

Whether it is through the extension of available indications, a better reimbursement or improved care, Real-world evidence generated from Real-world data are ultimately benefiting the patients. However, on the patient side, the mere production of RWD could also be beneficial, as the involvement of the patients in their care boosts adherence and helps detect complications and signs of relapse in real-time, to avoid wasting precious time at critical moments. For example, symptom monitoring through an online portal not only improves quality of life, patient satisfaction and ER utilization but also has a significant impact on extending patient’s overall survival [xv].

What are the key issues and opportunities for companies willing to use real-world data?

The EU has started funding many initiatives to bolster the generalization of RWD and RWE, and the EMA is strongly advocating for their use on a routine basis. However, Pharma companies should also marshal their resources to ensure they can seize the opportunity to improve their practice at every steps of their operations:

– Improve clinical trials through:

- Better understanding of patients and medical community needs

- Combining traditional RCTs, adaptative trials, pragmatic trials and collect data from more sources

- Pooling data from several trials to speed up trial execution and reduce unnecessary patient exposure

– Enrich Payer value proposition:

- Narrow the gap between efficacy and effectiveness

- Track the actual economic value of their treatments or of their competitors

– Isolate better responding population through biomarkers or socio-economic data

– Engage with patients in a compliant fashion, to better gather feedback and maximize treatment benefit

We see 3 key topics to be addressed by companies willing to build expertise in RWD:

1. Technical

Real-world data are rarely as clean as RCT data, since RCT data is homogenous, recorded in controlled conditions on well-defined patients, with identified confounding factors and strategies to minimize their influence. This implies several technical challenges to collect RWD in a timely and standardized manner despite the variability of the points of care, store them properly, especially within the framework of GDPR in Europe.

2. Talent

Parallel to the technical challenges mentioned above, analyzing RWD is more complicated than designing a priori a robust statistical analysis plan. It requires expert data scientist profiles, combining strong biostatistics knowledge and IT acumen to exploit the data lakes of structured and unstructured data of uneven quality.Beyond pure technical profiles, a new breed of cross-functional coordinators will be needed to ensure smooth information flow and alignment between all internal (R&D, Medical affairs, Regulatory affairs, Market Access, Patient centricity, Public affairs, IT, BI and analytics, Legal…) and external stakeholders (Regulators, Payers, Scientific and patient organizations, Insurers, Hospitals, …).

3. Governance

The importance of the coordinator position will go hand in hand with profound changes in governance, especially regarding the strategic role of these data on how to prioritize assets, to decide on the focus of future acquisitions or in-licensing. The questions of “who owns the data”, “what can be done with it” will be central in the generation and use of RWE, which will not accommodate the frequent siloed ways of working still at play in many pharma companies.

Conclusion

Far from opposing to one another, real-world data and data from clinical trial complement each other. Together, they could reduce time to market of innovative solutions, help both the payer and the industry derive better value from the treatments, inform clinical practice and optimize treatment allocation to the patients most-likely to have the highest benefit/risk ratio. However, to realize the full potential of RWD, changes need to happen in both the public (regulatory, payers, healthcare infrastructure) and private side to define the data standards as well as the best practice to collect, consolidate, present and use these data. With no doubt, companies integrating RWE at each step of the value chain will gain a competitive advantage but this requires an in-depth change in the way data are strategically considered and operationally collected, managed and analyzed.[1] Efficacy: benefits measured in a RCT setting[2] Effectiveness: benefits measured in clinical practice

___________________________________________________________

Sources :

[i] A. Bhatt, Perspect Clin Res. 2010 Jan-Mar; 1(1): 6–10.

[ii] Yeh et al. BMJ 2018;363:k5094

[iii] https://www.politico.eu/sponsored-content/making-the-eus-health-systems-fit-for-the-21st-century/, consulted March 12, 2019

[iv] Eichler et al, Clinical trials 2018 Vol 15 (S1) 27-32

[v] https://edps.europa.eu/data-protection/our-work/subjects/health_en consulted March 12, 2019

[vi] https://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2018/10/amazon-patents-alexa-tech-to-tell-if-youre-sick-depressed-and-sell-you-meds/ consulted March 12, 2019

[vii] Eichler, Real-World Evidence – an introduction; how is it relevant for the medicines regulatory system, EMA, London, April 2018

[viii] https://www.fdli.org/2018/08/update-fdas-historical-use-of-real-world-evidence/, consulted March 13, 2019

[ix] https://www.fiercepharma.com/pharma/janssen-agrees-to-rebate-cost-of-olysio-to-england-s-nhs-if-it-doesn-t-work consulted March 12, 2019

[x] https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta129/documents/department-of-health-summary-of-responder-scheme2

[xi] https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/910447, consulted March 16,2019

[xii] http://www.volumetovaluestudy.com/docs/Tracking%20the%20Shift%20From%20Volume%20to%20Value%20in%20Healthcare.pdf, consulted March 13, 2019

[xiii] Fiore et al. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2017;101(5):586-589.

[xiv] Boegemann et al. Anticancer Research November 2018 vol. 38 no. 11 6413-6422

[xv] https://meetinglibrary.asco.org/record/147027/abstract, consulted March 13, 2019