By Alexandre Bréant, Francis Turina-Malard and Bertrand Kleinmann, CEPTON Strategies

Pharma and Medtech companies are increasingly pushed to tie partnerships, driven by rising R&D costs, increasing bargaining power of purchasers, stronger regulatory constraints and the trend towards integrated care. Although Strategic Alliances seem long to initiate and complex to manage, their benefit-over-risk potential justify their increasing use. In this article, we review the basics of Strategic Alliances, describe their recent development in the healthcare industry, and give you some methodological keys to succeed in your Strategic Alliances.

What is a Strategic Alliance?

Business relationships between companies cover a continuum from spot commercial contracts to full acquisitions. In a spot contract, the amount of shared information is minimal, so are companies’ respective influence and commitment. On the other side, acquiring a company offers full control to the buyer, but also engages it to bear all the risks. The engagement duration is unlimited, and resources used are maximal. In between, Strategic Alliances enable two companies to jointly invest in the development of a common project in line with their respective strategies. Such alliances last longer and require a stronger commitment than spot contracts but contrary to M&A operations, they have a predefined end-point (time duration, level of investment/return, etc.).

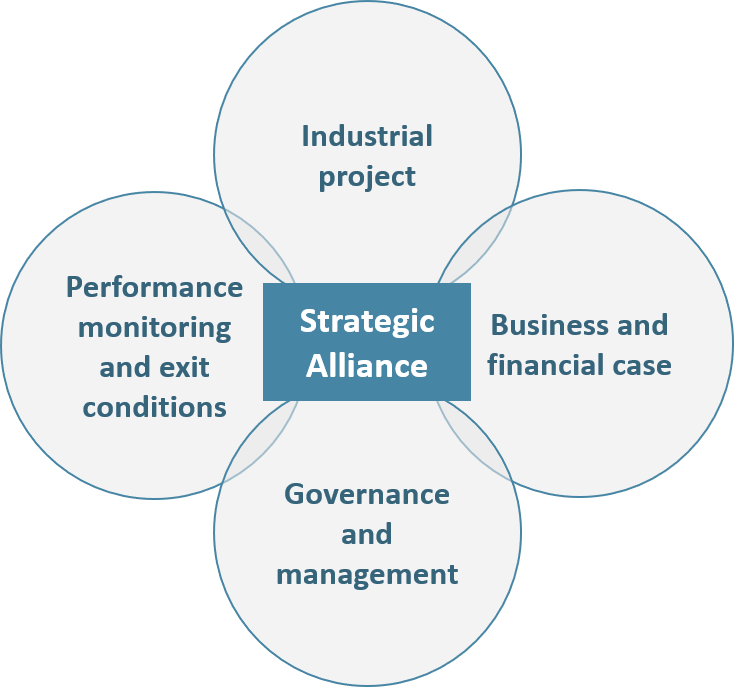

Figure 1: Strategic Alliances’ definition and characteristics

For a company, the main reason to form Strategic Alliances is to address growth opportunities that it could not address on its own, through sharing human, industrial or financial resources. The ASAP[1] claims that up to half of companies’ revenues are made from Strategic Alliances (a figure confirmed by a recent study from Columbia University: in a cohort of 1000 US public companies the share of revenues derived from alliances evolved from 5% in 1990 to 40% in 2010).

The Healthcare industry is the perfect example of an industry where companies need Strategic Alliances to grow: high research and development cost, high market-entry barriers, geographical specificities, need of large, highly-educated and well-implanted commercial teams to generate sales, etc.

A long-standing tradition of Strategic Alliances between Big Pharmas

For many decades, large pharmaceutical companies have been forming strategic partnerships between each other, or with small biotechnology companies, in order to increase their R&D productivity, expand their geographical footprint and/or share commercialization costs.

Increase R&D productivity

The difficulty, time and funds required to develop a new drug have skyrocketed in the last decades (~$2.5 billion and 10 years per drug in 2014[2]) due to increasingly complex diseases to treat (e.g. cancers), higher regulatory constraints and increased global competition. Consequently, Big Pharmas have been putting alliances at the heart of their R&D strategies. For instance, Abbvie has partnered with BMS through 3 collaboration programs, with Argenx in an up-to-$685m R&D deal and has joined the University of Chicago in a major research initiative. Abbvie also partnered in 2015 with Shanghai Pharmaceuticals to boost its clinical development pipeline in China.

Big Pharmas also intensively partner with young Biotechs to broaden their early stage portfolio and reduce risk of pipeline shortage through diversification. From Biotechs’ perspective, early stage alliances enhance their market value and provide access to Big Pharma expertise and infrastructure, which significantly reduces risk.

Enter a foreign market and share commercialization costs

Partnerships to develop sales in new geographies are also common in the Pharma industry, especially in quickly growing emergent markets as many barriers prevent foreign companies from entering these markets alone (regulatory approval, market access specificities, IP rights, infrastructure and commercial distribution network, understanding of local medical practices, etc). In 2014, Merck Serono and Lupin joined hands to tap several emerging markets: Brazil, Mexico, Indonesia, Eastern Europe. Lupin (Indian top 4 drug maker) develops and supplies finished products to Merck Serono, which remains the marketing authorization holder. Similarly, in 2017 Pfizer set up a JV with Zhejiang Hisun, a leading Chinese pharmaceutical company. Pfizer invested $250m in the JV which aims at developing, manufacturing and commercializing off-patent drugs in China. As tax law favors drugs manufactured in China, partnering with a local API manufacturer enabled Pfizer to cost-effectively penetrate this major market.

In Western markets, many co-commercialization agreements exist between Big Pharmas to reduce fixed costs. For instance, Amgen (in USA) and Pfizer (in the rest of the world) co-market Enbrel ($8.9b in 2016), while J&J and Merck have a similar partnership for Remicade ($8.2b in 2016).

A recent acceleration of Strategic Alliances activity triggered by the development of integrated care models and the rising importance of digital solutions

The last decade has seen the emergence of several new concepts (integrated care, personalized medicine, remote monitoring, telemedicine, etc.) that are bringing a fresh new paradigm in the management of healthcare. To transform these concepts into marketed solutions, Pharmaceutical companies need to acquire new expertise out of their traditional competency area. Strategic Alliances’ activity between Biopharmaceutical companies and Medtech/Tech companies (which have knowledge on Digital/Hardware and User Experience) will be needed to bring to market innovative end-to-end services.

Need for integrated care solutions

Pharmaceutical companies need to go “beyond the pill” and provide fully integrated solutions to healthcare centers, in which the medical device/diagnostic platform plays an increasingly important role. These integrated offers facilitate care delivery for physicians and centers, focus on patients Compliance/Quality of Life. For instance, Amgen France launched in 2017 a partnership in colorectal cancer with Biocartis. Biocartis develops Idylla, a Point-of-Care molecular diagnostics platform that provides physicians with actionable genetic biomarker data in 24 hours. This strategic partnership enables Amgen to propose a full offer to physicians who can test their colorectal cancerpatients and prescribe Amgen’s targeted therapy Vectibix to patients who have the appropriate genetic mutation.

Figure 2: Example of a joint Pharma/Medtech offer in an integrated care model

Chronic diseases monitoring

Long-term, remote monitoring of highly prevalent chronic diseases (cancers, diabetes, cardiology disorders, rheumatism, etc.) is becoming a central matter in today’s healthcare systems.

In oncology, drug makers have been increasingly developing oral therapies to satisfy patients and centers’ demand (1.4m cancer patients treated orally in France in 2017, i.e 30%.). This new model of care brings two major difficulties: poor patient’s compliance and complex management of serious side-effects, hence the need to develop smart and user-friendly digital monitoring solutions. Thess (Stiplastics), a mobile connected device able to monitor patients’ compliance and side effects is the typical device that adds strong value to an oral oncology therapy.

In diabetes, a JV – Onduo – was created in 2016 between Sanofi and Google Life Sciences to enable continuous monitoring of patients glycemia. Onduo aimed at combining Google’s expertise in miniaturized electronics, analytics, and consumer software with Sanofi’s diabetes program. In the terms, Google provided products and services worth $248 million while Sanofi fueled the JV with the same amount in cash. With such investments, companies were able to combine devices, software, medicine, and professional care to enable simple and intelligent disease management.

In the cardiovascular space, wearable ECGs are becoming commoditized. Apple’s latest watch includes an FDA-cleared ECG capable of detecting abnormal heart rhythms, which makes it a potential monitoring device for highly prevalent diseases like Atrial Fibrillation (6,6m patients in the US and 7,5m in the EU5 – 2016 data). Such wearable devices should trigger the interest of companies marketing cardiovascular drugs such as anticoagulants, the standard of care in Atrial Fibrillation. Considering the cost of anticoagulants to healthcare systems (the top 2 drugs, Eliquis and Xarelto, respectively generated $7.4b and $6.5b in 2017), governmental payers will be prone to promote such solutions and use the generated data to regularly evaluate drug efficacy and re-assess reimbursement levels.

Need for new competencies

Pharma companies also partner to acquire new competencies, like for instance data science experts, needed to develop solutions based on “artificial intelligence” (i.e. the analysis of big data set with modern algorithms). Because critical data on drugs and/or patients is at the heart of any AI-based solution, simple commercial contracts are too loose and risky to frame Pharma-AI collaborations. Acquiring an AI company is also risky as it could quickly become an empty shell. Hence, Strategic Alliances are ideally suited to enable Pharma and AI companies to co-develop and co-market solutions based on the analysis of large data sets to derive valuable insights on the safety and efficacy of a drug.

On the other side, Tech companies investing in healthcare opportunities may not be fully versed in navigating the complex regulatory landscape, a competency Pharma companies master. Moreover, Tech companies often have a consumer goods mindset, and are not used to targeting the specific customers pool constituted by physicians and healthcare centers. Pharma firms, with their extensive and knowledgeable salesforce that has formed long-standing relationships with physicians and hospitals can here provide highly valuable shortcuts to their Tech partner.

An increasing number of business alliances, but still with variable success

Despite the rising number and strategic importance of alliances between Pharma, Biotech, Medtech and “pure” Tech companies, recent surveys suggest a very high failure rate – more than half, according to the ASAP. Indeed, many alliances fall short of achieving maximum value for the partners involved. From our experience, the failure of alliances can be attributed to several factors:

- Assumption of success: partners usually do not anticipate failure, though it should be defined and planned for, so corrective actions can be taken readily to inverse the situation. Therefore, if the alliance must be dissolved, the damage (brand image, finance, etc.) can be minimized.

- Unclear objectives: alliances must be structured to meet clear goals. Defining both partners’ objectives and communicating them throughout each organization is essential.

- Lack of mutual understanding: understanding the partner, its own differences, its operating market structure (especially in the case of alliances between Pharma and Medtech/diagnostic), and its business philosophy is critical to the success of any alliance.

Your survival kit when engaging in a strategic partnership in the healthcare industry

Most difficulties met by partners after a few years usually come from divergent interests and/or a perceived inequity in the distribution of responsibilities, investments, risks or benefits. In most cases, these issues could have been anticipated earlier, when the alliance was designed and negotiated. As there is no “one size fits all” in strategic alliances, sound preparation coupled with continuous management is the only way to successfully drive an alliance in the long run.

At CEPTON, we have developed a rigorous methodology to design and drive Strategic Alliances. This methodology is presented hereafter:

1. Account for all the alliance constitutive elements from the start

In most cases, partnership discussions quickly focus on the legal translation of governance and benefit sharing matters, instead of considering all the parameters of the partnership from the very beginning:

– The project: the object of the partnership (e.g. new product development) must be clearly defined, as well as its initial perimeter, evolution conditions and time duration. Most importantly, each company must clearly define their vision of the future alliance independently of their own interest (financial, social, societal, image, etc.):

“When someone from Lilly sits at the table, he is representing the alliance, not Lilly. This is crucial to understand.”–Director of Alliance Management at Eli Lilly

Figure 3: The 4 pillars of an Alliance

– The business and financial cases: What is our project business potential? What are the financial resources required to meet our objectives? How much will each company contribute in terms of human resources, cash, immaterial knowledge, IP, equipment? In addition to answering these questions, partners should define clear principles regarding the alliance’s costs and revenues transparency.

– The alliance’s management and governance must be defined during the negotiation process. Both operational and executive management levels should be addressed for the entire duration of the partnership. The following elements should be addressed in priority:

o Operational structure (e.g. common engineering team)

o Commercialization of the project (e.g. first-responder right to any service demand, etc.)

o Alliance’s steering structure (e.g. nomination and revocation of directors)

Our experience shows that operational and strategic management levels should be clearly separated to maintain the alliance’s dynamics in the long run.

“Project management should not be confounded with alliance management. The alliance manager is responsible for communication, governance, culture, problem solving, conflict resolution, etc.” –Big Pharma executive

– Performance monitoring mechanisms and exit conditions, although often deemed secondary, are essential to be planned. By doing so, partners prevent themselves from uncontrollable value destruction (brand image, finance, regulatory, etc.) in case the Alliance does not fly as expected.

2. Follow a structured negotiation process

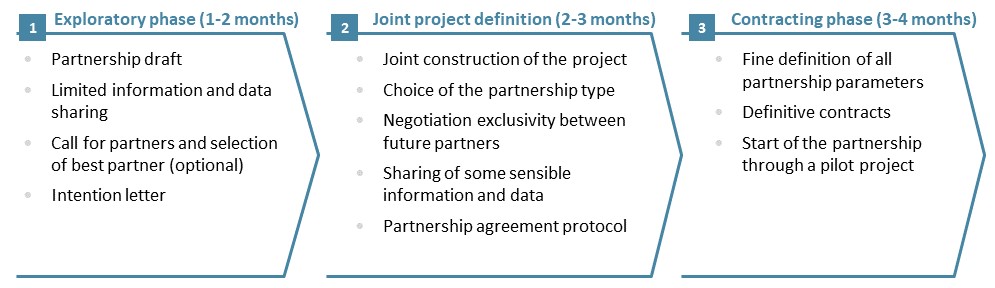

Embarking for a long-term partnership with another company, or even creating a JV, is a sensitive process which requires a lot of expertise: strategy, operations, finance, legal, human resources. Each partner should integrate the constraints associated with a share of governance, as well as the disclosure of sensitive information without which the project at the heart of the alliance could not be well defined. Our experience shows that a 3-phase process is required to account for the partners various points of view and to build solid foundation for the Strategic Alliance:

Figure 4: A three-Phase approach to build a strategic alliance

In the next decade, alliances will play an ever-more important role in Pharma and Medtech companies’ growth strategy

As we look to the future, we expect companies playing in the healthcare industry to continue to develop more and more Strategic Alliances. This trend to partnership acceleration is driven by a shift in care delivery paradigm requiring increasingly complex knowledge, skills and a wide range of services. In this context, Cepton will continue to provide decisive support to companies in their definition of strategic partnerships.

Information and points of view disclosed in this article are based on Cepton’s knowledge and on the following sources: Yoon (2017): “Inter-firm partnerships in the pharmaceutical industry” ; Lam (2004): “Why Alliances Fail?” ; Dr. Madden-Smith (2016): “The role of alliances in modern drug development” ; Bianchi (2011): “Open Innovation in the bio-pharmaceutical industry” ; Gottinger (2008): “Strategic Alliances in Global Biotech industries” ; Velis (2013): “Joint Ventures and Strategic Alliances: an alternative to M&A”

_______________________________________________

[1] Association of Strategic Alliances Professionals

[2] DiMasi study in 2014, and Mullin study in 2014